Universal Verification Methodology (UVM) 1.2 User’s Guide¶

March 23, 2020

Mandatory copyrights:

*Copyright © 2011 - 2015 Accellera. All rights reserved.*

Copyright © 2011 - 2015 Accellera Systems Initiative

(Accellera). All rights reserved.

Accellera Systems Initiative, 8698 Elk Grove Bldv Suite 1, #114, Elk

Grove, CA 95624, USA

Copyright © 2013 - 2015 Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. All

rights reserved.

Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), 7171 Southwest Parkway, Austin, TX

78735

Copyright © 2011 - 2015 Cadence Design Systems,

Inc. (Cadence). All rights reserved.

Cadence Design Systems, Inc., 2655 Seely Ave., San Jose, CA 95134,

USA.

Copyright © 2011 - 2015 Mentor Graphics, Corp. (Mentor). All

rights reserved.

Mentor Graphics, Corp., 8005 SW Boeckman Rd., Wilsonville, OR 97070,

USA

Copyright © 2013 - 2015 NVIDIA CORPORATION. All rights

reserved.

NVIDIA Corporation, 2701 San Tomas Expy, Santa Clara, CA 95050

Copyright © 2011 - 2015 Synopsys, Inc. (Synopsys). All rights

reserved.

Synopsys, Inc., 690 E. Middlefield Rd, Mountain View, CA 94043

Copyright © 2019 - 2023 Tuomas Poikela. All rights reserved.

This product is licensed under the Apache Software Foundation’s Apache License, Version 2.0, January 2004. The full license is available at: http://www.apache.org/licenses/.

Warning

This is semi-manual translation from the original SystemVerilog

UVM 1.2 User's Guide

to uvm-python. It is work-in-progress. It’s a work-in-progress and contains

still a lot of errors and references to SystemVerilog facilities. This will

be gradually fixed over time. Feel free to contribute to this userguide

with a pull request. Even small fixes will help in making it better!

Notices

While this guide offers a set of instructions to perform one or more specific verification tasks, it should be supplemented by education, experience, and professional judgment. Not all aspects of this guide may be applicable in all circumstances. The UVM 1.2 User’s Guide does not necessarily represent the standard of care by which the adequacy of a given professional service must be judged nor should this document be applied without consideration of a project’s unique aspects. The original SystemVerilog version of this guide has been approved through the Accellera consensus process and serves to increase the awareness of information and approaches in verification methodology. This guide may have several recommendations to accomplish the same thing and may require some judgment to determine the best course of action.

The uvm-python Class Reference represents the foundation used to create the UVM 1.2 User’s Guide. This guide is a way to apply the UVM 1.2 Class Reference, but is not the only way. Standards are an important ingredient to foster innovation and continues to encourage industry innovation based on its standards.

Table of Contents

0. Getting started¶

uvm-python uses cocotb Makefiles to launch the simulations and to control the

simulation arguments. It is also possible to use cocotb-test instead of

Makefiles. See README.md in the github repository for a minimal example. You

also need an HDL simulator. Verilator and Icarus Verilog are freely available

and can be used with uvm-python.

0.1 Installation¶

You can install uvm-python as a normal Python package. It is recommended to use [venv](https://docs.python.org/3/library/venv.html) to create a virtual environment for Python prior to installation:

git clone https://github.com/tpoikela/uvm-python.git

cd uvm-python

python -m pip install . # If venv is used

# Or without venv, and no sudo:

python -m pip install --user . # Omit --user for global installation

See [Makefile](test/examples/simple/Makefile) for working examples. You can

also use Makefiles in test/examples/simple as a

template for your project.

First example¶

uvm-python must be installed prior to running the example. Alternatively, you

can create a symlink to the uvm source folder:

cd test/examples/minimal

ln -s ../../../src/uvm uvm

You can find the source code for this example in test/examples/minimal. This example creates a test component, registers it with the UVM factory, and starts the test.

You can execute the example by running SIM=icarus make. Alternatively, you can

run it with SIM=verilator make:

# File: Makefile

TOPLEVEL_LANG ?= verilog

VERILOG_SOURCES ?= new_dut.sv

TOPLEVEL := new_dut

MODULE ?= new_test

include $(shell cocotb-config --makefiles)/Makefile.sim

The top-level module must match TOPLEVEL in Makefile:

// File: new_dut.sv

module new_dut(input clk, input rst, output[7:0] byte_out);

assign byte_out = 8'hAB;

endmodule: new_dut

The Python test file name must match MODULE in Makefile:

# File: new_test.py

import cocotb

from cocotb.triggers import Timer

from uvm import *

class NewTest(UVMTest):

async def run_phase(self, phase):

phase.raise_objection(self)

await Timer(100, "NS")

phase.drop_objection(self)

uvm_component_utils(NewTest)

@cocotb.test()

async def test_dut(dut):

await run_test('NewTest')

To run the example, execute:

SIM=icarus make

1. Overview¶

This chapter provides a quick overview of UVM by going through the typical testbench architecture and introducing the terminology used throughout this User’s Guide. Then, it also touches upon the UVM Base Class Library (BCL) developed by Accellera.

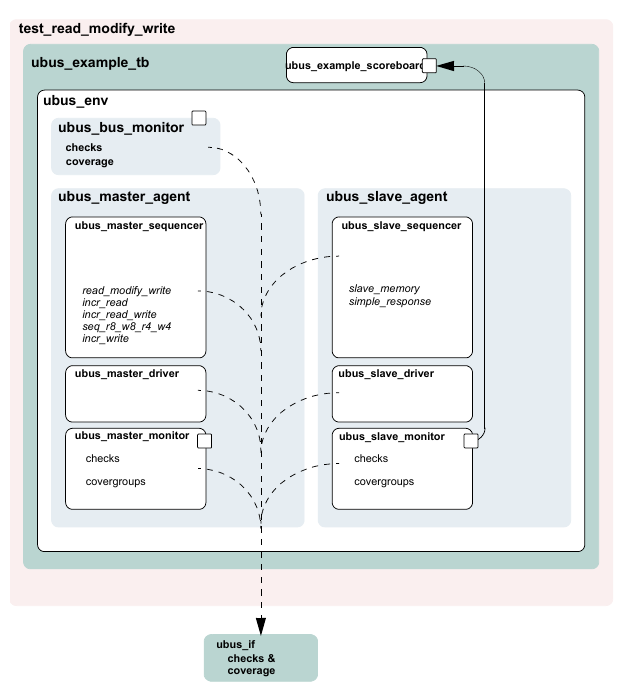

1.1 The Typical UVM Testbench Architecture¶

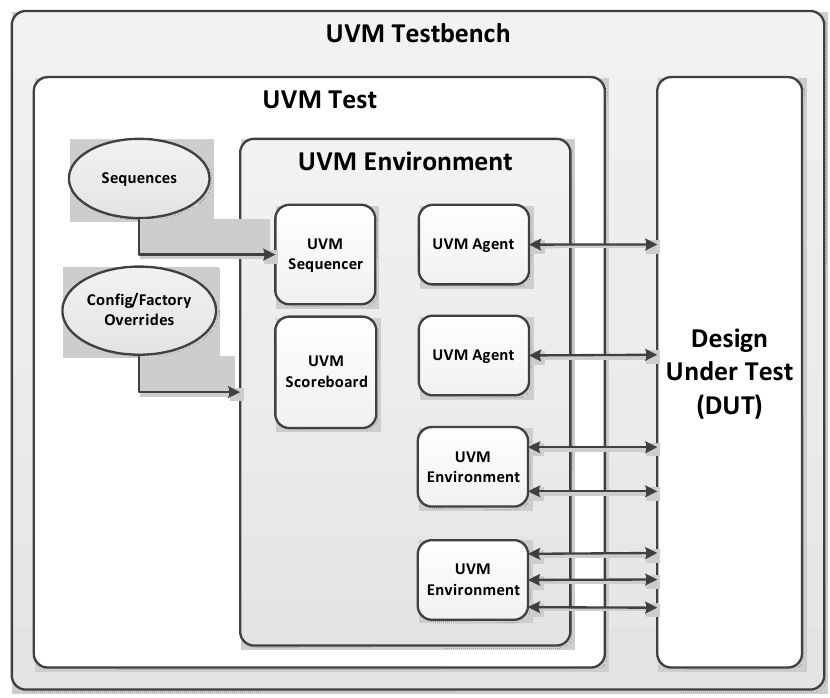

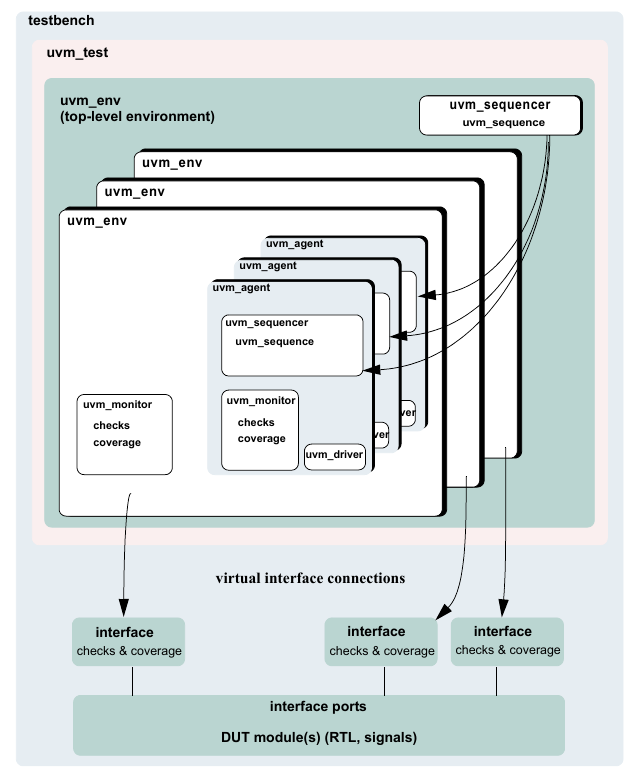

The UVM Class Library provides generic utilities, such as component hierarchy, transaction library model (TLM), configuration database, etc., which enable the user to create virtually any structure he/she wants for the testbench. This section provides some broad guidelines for a type of recommended testbench architecture by using one viewpoint of this architecture in an effort to introduce the terminology used throughout this User’s Guide, as shown in Figure 1.

NB: This particular representation is not intended to represent all possible testbench architectures or every type use of UVM in the electronic design automation (EDA) industry.

Typical UVM Testbench Architecture¶

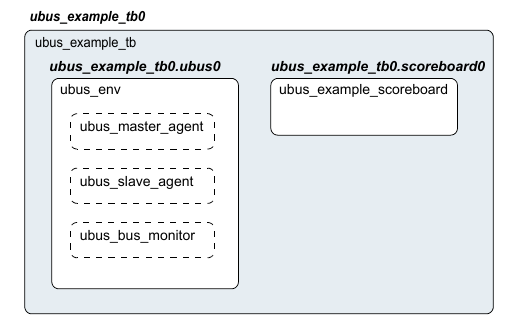

1.1.1 UVM Testbench¶

The UVM Testbench is simply a Python function decorated with @cocotb.test. The Design under Test (DUT) module is passed to the testbench as an object, and no explicit signal connections have to be made by the user. This is an advantage over SystemVerilog-based testbenches where DUT-module has to be instantiated and signal connections have to be made explicitly. The UVM Test class can be declared in a separate file and then imported into the testbench. If the verification collaterals include module-based components, they should be instantiated in a wrapper HDL module outside Python code. The UVM Test is dynamically instantiated at run-time, allowing the an HDL DUT to be compiled/elaborated once, and run with many different tests.

Note that in some architectures, the Testbench term is used to refer to a special module that encapsulates verification collaterals only, which in turn are integrated up with the DUT.

1.1.2 UVM Test¶

The UVMTest is the top-level UVM Component in the UVM Testbench.

The UVM Test typically performs three main functions: Instantiates

the top-level environment, configures the environment (via configuration

objects, factory overrides or the configuration database), and applies

stimulus by invoking UVM Sequences through the environment to the DUT.

Typically, there is one base UVM Test with the UVM Environment instantiation and other common items. Then, other individual tests will extend this base test and configure the environment differently or select different sequences to run.

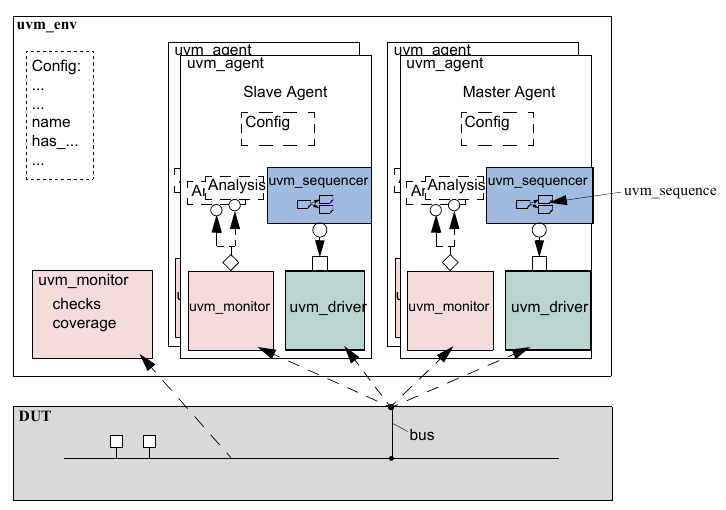

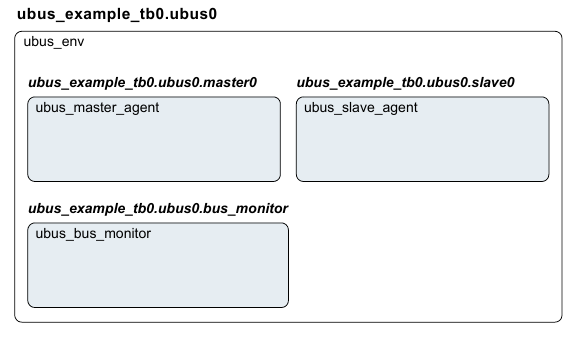

1.1.3 UVM Environment¶

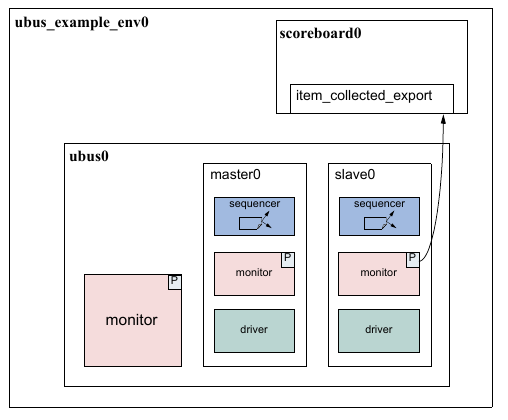

The UVM Environment is a hierarchical component that groups together other verification components that are interrelated. Typical components that are usually instantiated inside the UVM Environment are UVM Agents, UVM Scoreboards, or even other UVM Environments. The top-level UVM Environment encapsulates all the verification components targeting the DUT.

For example: In a typical system on a chip (SoC) UVM Environment, you will find one UVM Environment per IP (e.g., PCIe Environment, USB Environment, Memory Controller Environment, etc.). Sometimes, those IP Environments are grouped together into Cluster Environments or subsystem environments (e.g., IO Environment, Processor Environment, etc.) that are grouped together eventually in the top-level SoC Environment.

1.1.4 UVM Scoreboard¶

The UVM Scoreboard’s main function is to check the behavior of a certain DUT. The UVM Scoreboard usually receives transactions carrying inputs and outputs of the DUT through UVM Agent analysis ports (connections are not depicted in Figure 1), runs the input transactions through some kind of a reference model (also known as the predictor) to produce expected transactions, and then compares the expected output versus the actual output.

There are different methodologies on how to implement the scoreboard, the nature of the reference model, and how to communicate between the scoreboard and the rest of the testbench.

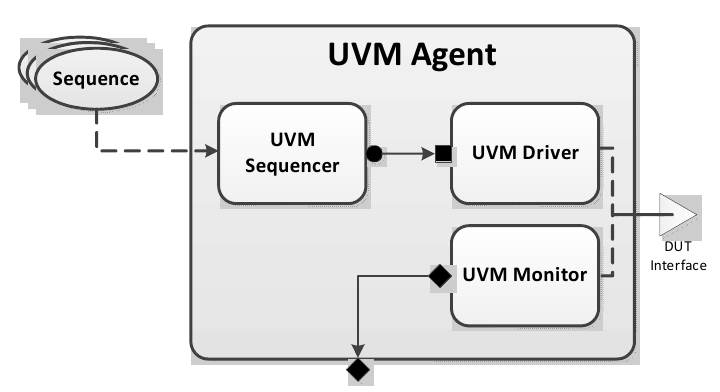

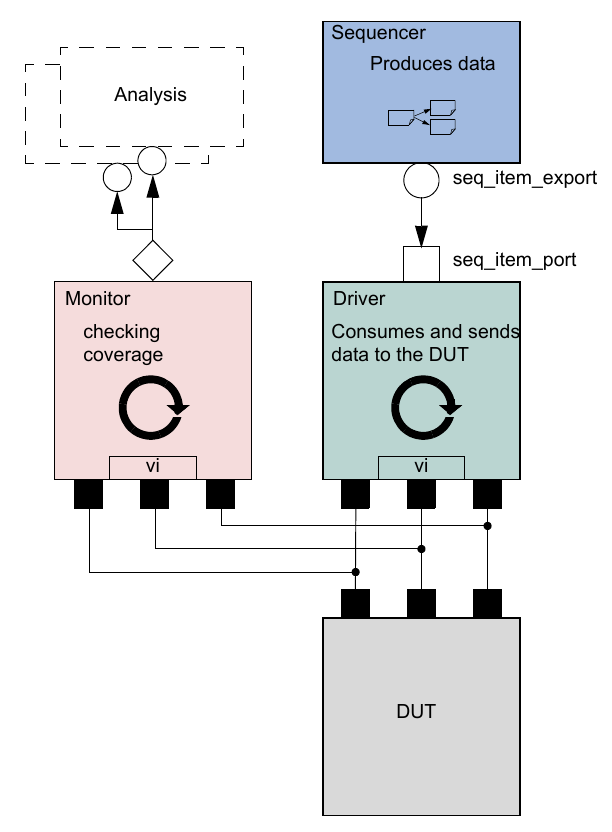

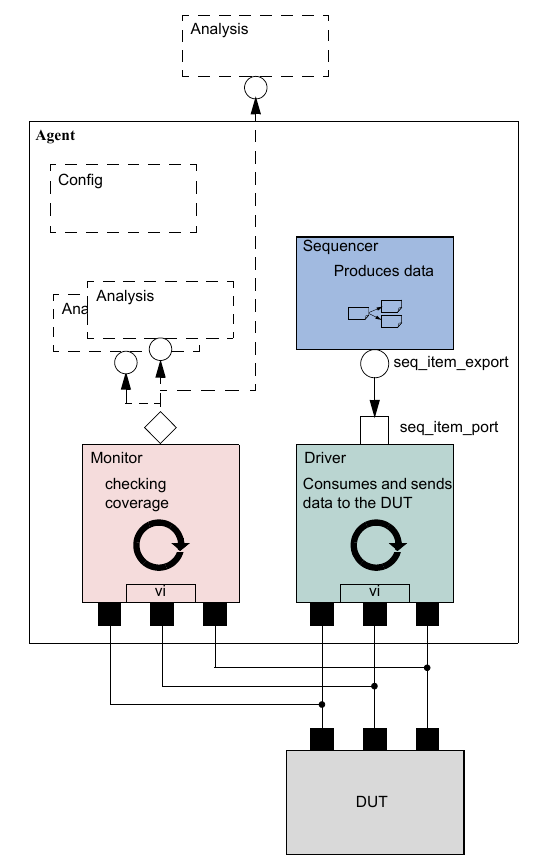

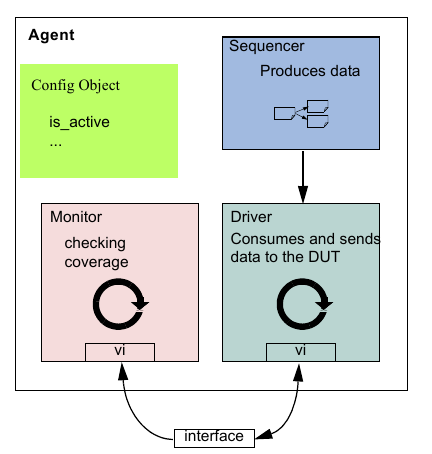

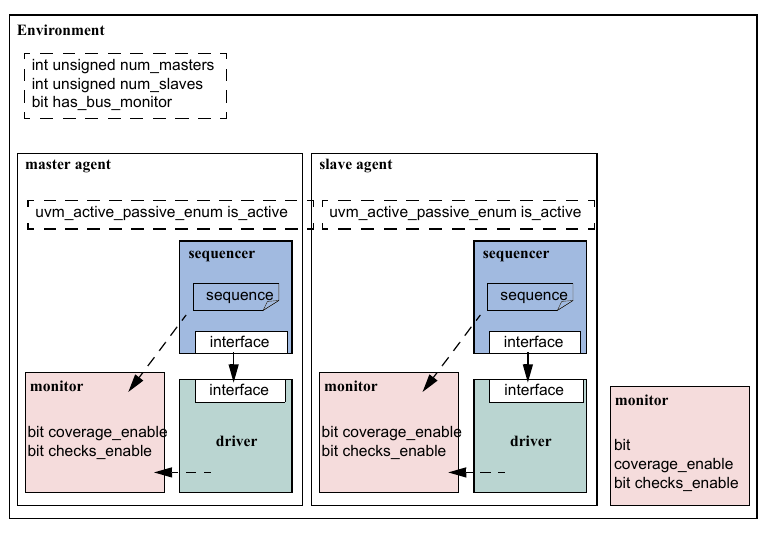

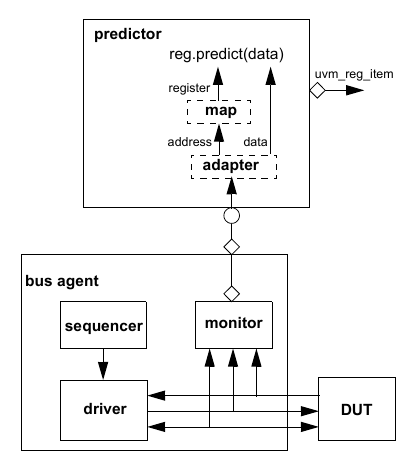

1.1.5 UVM Agent¶

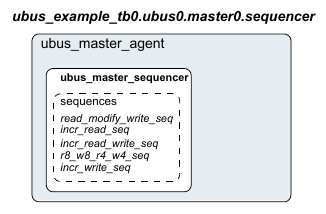

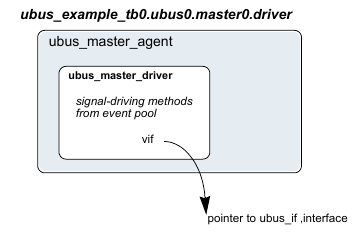

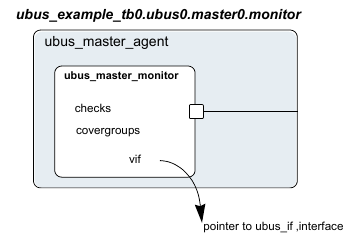

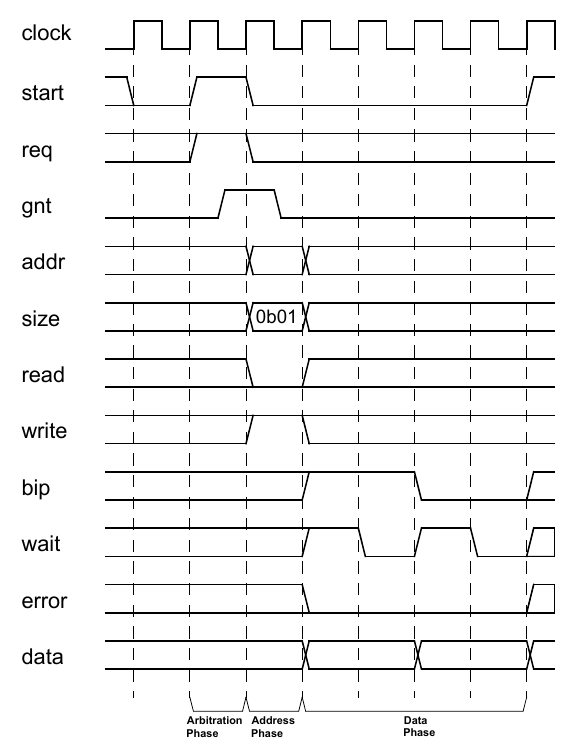

The UVM Agent is a hierarchical component that groups together other verification components that are dealing with a specific DUT interface (see Figure 2). A typical UVM Agent includes a UVM Sequencer to manage stimulus flow, a UVM Driver to apply stimulus on the DUT interface, and a UVM Monitor to monitor the DUT interface. UVM Agents might include other components, like coverage collectors, protocol checkers, a TLM model, etc.

UVM Agent¶

The UVM Agent needs to operate both in an active mode (where it is capable of generating stimulus) and a passive mode (where it only monitors the interface without controlling it).

1.1.6 UVM Sequencer¶

The UVM Sequencer serves as an arbiter for controlling transaction flow from multiple stimulus sequences. More specifically, the UVM Sequencer controls the flow of UVM Sequence Items transactions generated by one or more UVM Sequences.

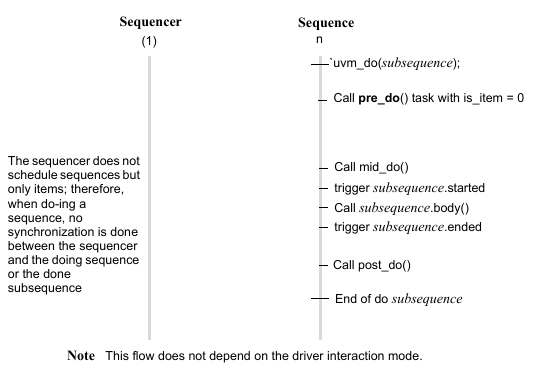

1.1.7 UVM Sequence¶

A UVM Sequence is an object that contains a behavior for generating stimulus. UVM Sequences are not part of the component hierarchy. UVM Sequences can be transient or persistent. A UVM Sequence instance can come into existence for a single transaction, it may drive stimulus for the duration of the simulation, or anywhere in-between. UVM Sequences can operate hierarchically with one sequence, called a parent sequence, invoking another sequence, called a child sequence.

To operate, each UVM Sequence is eventually bound to a UVM Sequencer. In

practice this means that UVMSequence.start receives the sequencer as

an argument. Multiple UVM Sequence instances can be bound to the same

UVM Sequencer. Top-level sequences do not have to run on a sequencer,

and can start other sequences instead.

1.1.8 UVM Driver¶

The UVM Driver receives individual UVM Sequence Item transactions from the UVM Sequencer and applies (drives) it on the DUT Interface. Thus, a UVM Driver spans abstraction levels by converting transaction-level stimulus into pin-level stimulus. It also has a TLM port to receive transactions from the Sequencer and access to the DUT interface in order to drive the signals.

1.1.9 UVM Monitor¶

The UVM Monitor samples the DUT interface and captures the information there in transactions that are sent out to the rest of the UVM Testbench for further analysis. Thus, similar to the UVM Driver, it spans abstraction levels by converting pin-level activity to transactions. In order to achieve that, the UVM Monitor typically has access to the DUT interface and also has a TLM analysis port to broadcast the created transactions through.

The UVM Monitor can perform internally some processing on the transactions produced (such as coverage collection, checking, logging, recording, etc.) or can delegate that to dedicated components connected to the monitor’s analysis port.

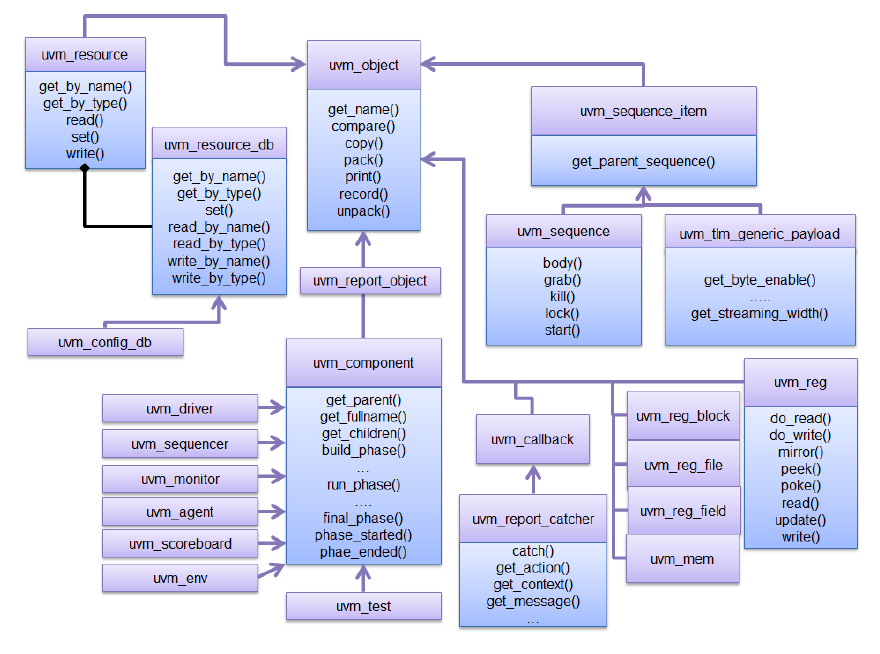

1.2 The UVM Class Library¶

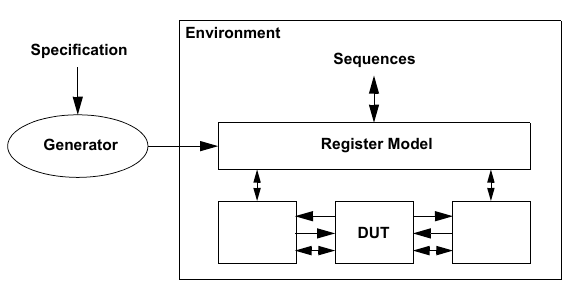

The UVM Class Library provides all the building blocks you need to quickly develop well-constructed, reusable, verification components and test environments. The library consists of base classes, utilities, and macros. Figure 3 shows a subset of those classes.

Components may be encapsulated and instantiated hierarchically and are controlled through an extendable set of phases to initialize, run, and complete each test. These phases are defined in the base class library, but can be extended to meet specific project needs. See the UVM 1.2 Class Reference for more information.

UVM Class Diagram¶

The advantages of using the UVM Class Library include:

a) A robust set of built-in features—The UVM Class Library provides many features that are required for verification, including complete implementation of printing, copying, test phases, factory methods, and more. b) Correctly-implemented UVM concepts—Each component in the block diagram in Figure 1 and Figure 2 can be derived from a corresponding UVM Class Library component. Using these baseclass elements increases the readability of your code since each component’s role is predetermined by its parent class.

The UVM Class Library also provides various utilities to simplify the development and use of verification environments. These utilities support configurability by providing a standard resource sharing database. They support debugging by providing a user-controllable messaging utility for failure reporting and general reporting purposes. They support testbench construction by providing a standard communication infrastructure between verification components (TLM) and flexible verification environment construction (UVM factory). Finally, they also provide mixins for allowing more compact coding styles. These mixins offer similar capabilities as macros in the SystemVerilog (SV) version.

This User’s Guide will touch on most of these utilities; for the complete list, see the UVM 1.2 Class Reference.

2. Transaction-Level Modeling (TLM)¶

2.1 Overview¶

One of the keys to verification productivity is to think about the problem at a level of abstraction that makes sense. When verifying a DUT that handles packets flowing back and forth, or processes instructions, or performs other types of functionality, you must create a verification environment that supports the appropriate abstraction level. While the actual interface to the DUT ultimately is represented by signal-level activity, experience has shown that it is necessary to manage most of the verification tasks, such as generating stimulus and collecting coverage data, at the transaction level, which is the natural way engineers tend to think of the activity of a system.

UVM provides a set of transaction-level communication interfaces and channels that you can use to connect components at the transaction level. The use of TLM interfaces isolates each component from changes in other components throughout the environment. When coupled with the phased, flexible build infrastructure in UVM, TLM promotes reuse by allowing any component to be swapped for another, as long as they have the same interfaces. This concept also allows UVM verification environments to be assembled with a transaction-level model of the DUT, and the environment to be reused as the design is refined to RTL. All that is required is to replace the transaction-level model with a thin layer of compatible components to convert between the transaction-level activity and the pin-level activity at the DUT.

The well-defined semantics of TLM interfaces between components also provide the ideal platform for implementing mixed-language verification environments. In addition, TLM provides the basis for easily encapsulating components into reusable components, called verification components, to maximize reuse and minimize the time and effort required to build a verification environment.

This chapter discusses the essential elements of transaction-level communication in UVM, and illustrates the mechanics of how to assemble transaction-level components into a verification environment. Later in this document we will discuss additional concerns in order to address a wider set of verification issues. For now, it is important to understand these foundational concepts first.

2.2 TLM, TLM-1, and TLM-2.0¶

TLM, transaction-level modeling, is a modeling style for building highly abstract models of components and systems. It relies on transactions (see Section 2.3.1.1), objects that contain arbitrary, protocol-specific data to abstractly represent lower-level activity. In practice, TLM refers to a family of abstraction levels beginning with cycle-accurate modeling, the most abstract level, and extending upwards in abstraction as far as the eye can see. Common transaction-level abstractions today include: cycle-accurate, approximately-timed, loosely-timed, untimed, and token-level.

The acronym TLM also refers to a system of code elements used to create transaction-level models. TLM-1 and TLM-2.0 are two TLM modeling systems which have been developed as industry standards for building transaction-level models. Both were built in SystemC and standardized within the TLM Working Group of the Open SystemC Initiative (OSCI). TLM-1 achieved standardization in 2005 and TLM-2.0 became a standard in 2009. OSCI merged with Accellera in 2013 and the current SystemC standard used for reference is IEEE 1666-2011.

TLM-1 and TLM-2.0 share a common heritage and many of the same people who developed TLM-1 also worked on TLM-2.0. Otherwise, they are quite different things. TLM-1 is a message passing system. Interfaces are either untimed or rely on the target for timing. None of the interfaces provide for explicit timing annotations. TLM-2.0, while still enabling transfer of data and synchronization between independent processes, is mainly designed for high performance modeling of memory-mapped bus-based systems. A subset of both these facilities has been implemented in uvm-python and is available as part of UVM.

2.3 TLM-1 Implementation¶

The following subsections specify how TLM-1 is to be implemented in uvm-python.

2.3.1 Basics¶

Before you can fully understand how to model verification at the transaction level, you must understand what a transaction is.

2.3.1.1 Transactions¶

In UVM, a transaction is a class object that includes whatever information is needed to model a unit of communication between two components. In the most basic example, a simple bus protocol transaction to transfer information would be modeled as follows:

class simple_trans(UVMSequenceItem);

def __init__(self, name):

super().__init__(name)

self.data = 0

self.rand('data')

self.addr = 0x0

self.rand('addr')

self.kind = WRITE

self.rand('kind', [WRITE, READ])

self.constraint(lambda addr: addr < 0x2000)

The transaction object includes variables, constraints, and other fields and methods necessary for generating and operating on the transaction. Obviously, there is often more than just this information that is required to fully specify a bus transaction. The amount and detail of the information encapsulated in a transaction is an indication of the abstraction level of the model. For example, the simple_trans transaction above could be extended to include more information, such as the number of wait states to inject, the size of the transfer, or any number of other properties. The transaction could also be extended to include additional constraints. It is also possible to define higher-level transactions that include some number of lower-level transactions. Transactions can thus be composed, decomposed, extended, layered, and otherwise manipulated to model whatever communication is necessary at any level of abstraction.

2.3.1.2 Transaction-Level Communication¶

Transaction-level interfaces define a set of methods that use transaction objects as arguments. A TLM port defines the set of methods (the application programming interface (API)) to be used for a particular connection, while a TLM export supplies the implementation of those methods. Connecting a port to an export allows the implementation to be executed when the port method is called.

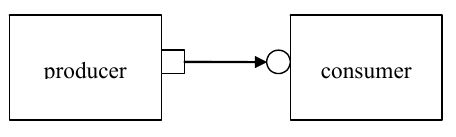

2.3.1.3 Basic TLM Communication¶

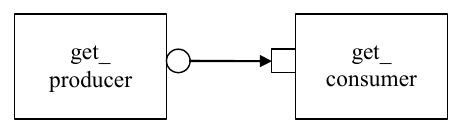

The most basic transaction-level operation allows one component to put a transaction to another. Consider Figure 4.

Single Producer/Consumer¶

The square box on the producer indicates a port and the circle on the consumer indicates the export. The producer generates transactions and sends them out its put_port:

class producer (UVMComponent);

def __init__(self, name, parent):

super().__init__(name, parent)

self.put_port = UVMBlockingPutPort(“put_port”, self)

...

async def run(self):

for _ in range(N):

t = simple_trans()

# Generate t.

await self.put_port.put(t);

NOTE—The uvm_*_port is parameterized by the transaction type that will be communicated. This may either be specified directly or it may be a parameter of the parent component.

The actual implementation of the put() call is supplied by the consumer:

class consumer(UVMComponent):

def __init__(self, name, parent):

super().__init__(name, parent)

self.put_export = UVMBlockingPutImp(“put_export”, self)

# 2 parameters ...

async def put(self, t):

if t.kind == READ:

# Do read.

elif t.kind == WRITE:

# Do write.

NOTE—The UVM*Imp takes two parameters: the type of the transaction and the type of the object that declares the method implementation.

NOTE—The semantics of the put operation are defined by TLM. In this

case, the put() call in the producer will block until the consumer’s

put implementation is complete. Other than that, the operation of

producer is completely independent of the put implementation

(UVMPutImp). In fact, consumer could be replaced by another

component that also implements put and producer will continue to work

in exactly the same way. The modularity provided by TLM fosters an

environment in which components may be easily reused since the

interfaces are well defined.

The converse operation to put is get. Consider Figure 5.

Consumer gets from Producer¶

In this case, the consumer requests transactions from the producer via its get port:

class get_consumer (UVMComponent):

def __init__(self, name, parent):

super().__init__(name, parent)

self.get_port = UVMBlockingGetPort(“get_port”, self)

...

async def run_phase(self, phase):

for _ in range(N):

# Generate t.

t = simple_trans()

await self.get_port.get(t);

The get() implementation is supplied by the producer:

class get_producer (UVMComponent):

def __init__(self, name, parent):

super().__init__(name, parent)

self.get_export = UVMBlockingGetImp("get_export", self)

async def get(self, t):

tmp = simple_trans()

// Assign values to tmp.

t.copy(tmp)

As with put() above, the get_consumer’s get() call will block until the get_producer’s method completes. In TLM terms, put() and get() are blocking methods.

NOTE — In both these examples, there is a single process running, with control passing from the port to the export and back again. The direction of data flow (from producer to consumer) is the same in both examples.

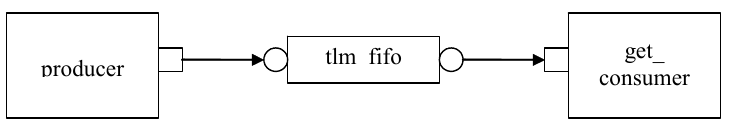

2.3.1.4 Communicating between Processes¶

In the basic put example above, the consumer will be active only when

its put() method is called. In many cases, it may be necessary for

components to operate independently, where the producer is creating

transactions in one process while the consumer needs to operate on

those transactions in another. UVM provides the UVMTLMFIFO channel

to facilitate such communication. The UVMTLMFIFO implements all of

the TLM interface methods, so the producer puts the transaction into

the UVMTLMFIFO, while the consumer independently gets the

transaction from the fifo, as shown in Figure 6.

Using a uvm_tlm_fifo¶

When the producer puts a transaction into the fifo, it will block if the fifo is full, otherwise it will put the object into the fifo and return immediately. The get operation will return immediately if a transaction is available (and will then be removed from the fifo), otherwise it will block until a transaction is available. Thus, two consecutive get() calls will yield different transactions to the consumer. The related peek() method returns a copy of the available transaction without removing it. Two consecutive peek() calls will return copies of the same transaction.

2.3.1.5 Blocking versus Nonblocking¶

The interfaces that we have looked at so far are blocking—the tasks block execution until they complete; they are not allowed to fail. There is no mechanism for any blocking call to terminate abnormally or otherwise alter the flow of control. They simply wait until the request is satisfied. In a timed system, this means that time may pass between the time the call was initiated and the time it returns.

In contrast, a nonblocking call returns immediately. The semantics of a nonblocking call guarantee that the call returns in the same delta cycle in which it was issued, that is, without consuming any time, not even a single delta cycle. In UVM, nonblocking calls are modeled as functions:

class consumer (UVMComponent):

def __init__(self, name, parent):

super().__init__(name, parent)

self.get_port = UVMGetPort("get_port", self)

async def run_phase(self phase):

...

for _ in range(10):

t = []

if (self.get_port.try_get(t)) # Do something with t[0]

...

If a transaction exists, it will be returned in the argument and the function call itself will return TRUE. If no transaction exists, the function will return FALSE. Similarly, with try_peek(). The try_put() method returns TRUE if the transaction is sent.

2.3.1.6 Connecting Transaction-Level Components¶

With ports and exports defined for transaction-level components, the actual connection between them is accomplished via the connect() method in the parent (component or env), with an argument that is the object (port or export) to which it will be connected. In a verification environment, the series of connect() calls between ports and exports establishes a netlist of peer-to-peer and hierarchical connections, ultimately terminating at an implementation of the agreed-upon interface. The resolution of these connections causes the collapsing of the netlist, which results in the initiator’s port being assigned to the target’s implementation. Thus, when a component calls:

put_port.put(t)

the connection means that it actually calls:

target.put_export.put(t)

where target is the connected component.

2.3.1.7 Peer-to-Peer connections¶

When connecting components at the same level of hierarchy, ports are always connected to exports. All connect() calls between components are done in the parent’s connect() method:

class my_env(UVMEnv):

...

def connect_phase(self, phase);

# component.port.connect(target.export);

self.producer.blocking_put_port.connect(fifo.put_export);

self.get_consumer.get_port.connect(fifo.get_export);

...

2.3.1.8 Port/Export Compatibility¶

Another advantage of TLM communication in UVM is that all TLM connections are checked for compatibility before the test runs. In order for a connection to be valid, the export must provide implementations for at least the set of methods defined by the port and the transaction type parameter for the two must be identical. For example, a blocking_put_port, which requires an implementation of put() may be connected to either a blocking_put_export or a put_export. Both exports supply an implementation of put(), although the put_export also supplies implementations of try_put() and can_put().

2.3.2 Encapsulation and Hierarchy¶

The use of TLM interfaces isolates each component in a verification environment from the others. The environment instantiates a component and connects its ports/exports to its neighbor(s), independent of any further knowledge of the specific implementation. Smaller components may be grouped hierarchically to form larger components. Access to child components is achieved by making their interfaces visible at the parent level. At this level, the parent simply looks like a single component with a set of interfaces on it, regardless of its internal implementation.

2.3.2.1 Hierarchical Connections¶

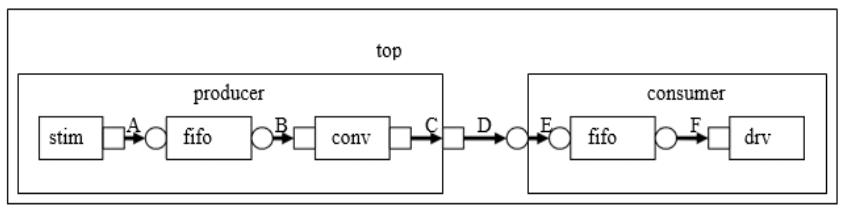

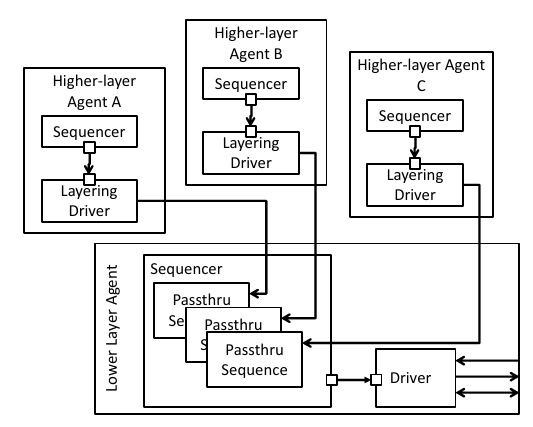

Making connections across hierarchical boundaries involves some additional issues, which are discussed in this section. Consider the hierarchical design shown in Figure 7.

Hierarchy in TLM¶

The hierarchy of this design contains two components, producer and

consumer. producer contains three components, stim, fifo, and conv.

consumer contains two components, fifo and drv. Notice that, from the

perspective of top, the producer and consumer appear identical to

those in Figure 4, in which the producer’s put_port is connected to

the consumer’s put_export. The two fifos are both unique instances of

the same UVMTLMFIFO component.

In Figure 7, connections A, B, D, and F are standard peer-to-peer connections as discussed above. As an example, connection A would be coded in the producer’s connect() method as:

gen.put_port.connect(fifo.put_export);

Connections C and E are of a different sort than what have been shown. Connection C is a port-to-port connection, and connection E is an export-to-export connection. These two kinds of connections are necessary to complete hierarchical connections. Connection C imports a port from the outer component to the inner component. Connection E exports an export upwards in the hierarchy from the inner component to the outer one. Ultimately, every transaction-level connection must resolve so that a port is connected to an export. However, the port and export terminals do not need to be at the same place in the hierarchy. We use port-to-port and export-to-export connections to bring connectors to a hierarchical boundary to be accessed at the next-higher level of hierarchy.

For connection E, the implementation resides in the fifo and is exported up to the interface of consumer. All export-to-export connections in a parent component are of the form:

export.connect(subcomponent.export)

so connection E would be coded as:

class consumer(UVMComponent):

put_export = uvm_put_export(trans)

fifo = uvm_tlm_fifo(trans)

def connect_phase(self, phase):

super().connect_phase(phase)

self.put_export.connect(self.fifo.put_export)

self.bfm.get_port.connect(self.fifo.get_export)

Conversely, port-to-port connections are of the form:

subcomponent.port.connect(port);

so connection C would be coded as:

class producer(UVMComponent):

put_port = uvm_put_port()

c = conv()

def connect_phase(self, phase):

super().connect_phase(phase)

self.c.put_port.connect(self.put_port)

# ...

2.3.2.2 Connection Types¶

Table 1 summarizes connection types and elaboration functions.

Table 1—TLM Connection Types

port-to-export |

comp1.port.connect(comp2.export); |

port-to-port |

subcomponent.port.connect(port); |

export-to-export |

export.connect(subcomponent.export); |

NOTE—The argument to the port.connect() method may be either an export or a port, depending on the nature of the connection (that is, peer-to-peer or hierarchical). The argument to export.connect() is always an export of a child component.

2.3.3 Analysis Communication¶

The put/get communication as described above allows verification components to be created that model the “operational” behavior of a system. Each component is responsible for communicating through its TLM interface(s) with other components in the system in order to stimulate activity in the DUT and/or respond its behavior. In any reasonably complex verification environment, however, particularly where randomization is applied, a collected transaction should be distributed to the rest of the environment for end-to-end checking (scoreboard), or additional coverage collection.

The key distinction between the two types of TLM communication is that the put/get ports typically require a corresponding export to supply the implementation. For analysis, however, the emphasis is on a particular component, such as a monitor, being able to produce a stream of transactions, regardless of whether there is a target actually connected to it. Modular analysis components are then connected to the analysis_port, each of which processes the transaction stream in a particular way.

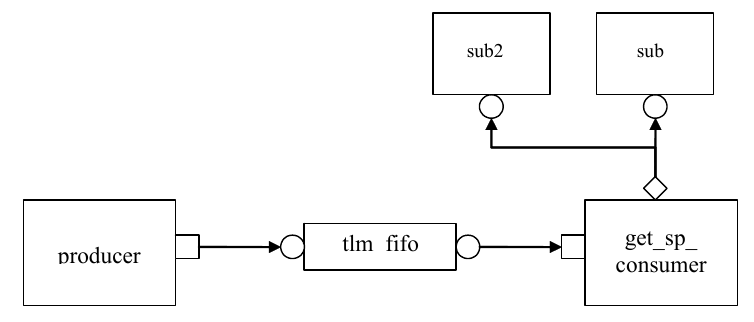

2.3.3.1 Analysis Ports¶

The UVMAnalysisPort (represented as a diamond on the monitor in

Figure 8) is a specialized TLM port whose interface consists of a

single function, write(). The analysis port contains a list of

analysis_exports that are connected to it. When the component calls

analysis_port.write(), the analysis_port cycles through the list and

calls the write() method of each connected export. If nothing is

connected, the write() call simply returns. Thus, an analysis port

may be connected to zero, one, or many analysis exports, but the

operation of the component that writes to the analysis port does not

depend on the number of exports connected. Because write() is a void

function, the call will always

complete in the same delta cycle, regardless of how many components

(for example, scoreboards, coverage collectors, and so on) are

connected.

Analysis Communication¶

Code example:

class get_consumer_with_ap(get_consumer):

def __init__(self, name, parent):

super().__init__(name, parent)

self.ap = UVMAnalysisPort(“analysis_port”, self)

...

async def run_phase(self, phase):

...

for i in range(10):

t = []

if self.get_port.get(t):

# Do something with t.

tx = t[0]

self.ap.write(tx) # Write transaction.

In the parent environment, the analysis port gets connected to the analysis export of the desired components, such as coverage collectors and scoreboards.

2.3.3.2 Analysis Exports¶

As with other TLM connections, it is up to each component connected to an analysis port to provide an implementation of write() via an analysis_export. The UVMSubscriber base component can be used to simplify this operation, so a typical analysis component would extend UVMSubscriber as:

class sub1(UVMSubscriber):

# my_env env;

def write(self, t);

# Call desired functionality in parent.

As with put() and get() described above, the TLM connection between an analysis port and export, allows the export to supply the implementation of write(). If multiple exports are connected to an analysis port, the port will call the write() of each export, in order. Since all implementations of write() must be functions, the analysis port’s write() function completes immediately, regardless of how many exports are connected to it:

class my_env(UVMEnv):

# get_component_with_ap g;

# sub1 s1; sub2 s2;

def __init__(self, name, parent):

super().__init__(name,parent)

self.s1 = sub1("s1")

self.s1.env = self

self.s2 = sub2("s2")

self.s2.env = self

self.g = get_component_with_ap()

endfunction

def connect_phase(self, phase):

self.g.ap.connect(s1.analysis_export);

# to illustrate analysis port can be connected to multiple

# subscribers; usually the subscribers are in separate components

self.g.ap.connect(s2.analysis_export);

When multiple subscribers are connected to an analysis_port, each is passed a pointer to the same transaction object, the argument to the write() call. Each write() implementation must make a local copy of the transaction and then operate on the copy to avoid corrupting the transaction contents for any other subscriber that may have received the same pointer.

UVM also includes an analysis_fifo, which is a uvm_tlm_fifo that also includes an analysis export, to allow blocking components access to the analysis transaction stream. The analysis_fifo is unbounded, so the monitor’s write() call is guaranteed to succeed immediately. The analysis component may then get the transactions from the analysis_fifo at its leisure.

2.4 TLM-2.0 Implementation¶

Warning

TLM-2.0 interaction/integration with SystemC is untested at this point of development. This depends heavily on the simulation support as well.

The following subsections specify how TLM-2.0 is to be implemented in Python.

2.4.1 Generic Payload¶

TLM-2.0 defines a base object, called the generic payload, for

moving data between components. In SystemC, this is the primary

transaction vehicle. In uvm-python, this is the default

transaction type, but it is not the only type that can be used (as

will be explained more fully in Section 2.4.2).

2.4.1.1 Attributes¶

Each attribute in the SystemC version has a corresponding member in

the uvm-python generic payload:

m_address # type: int

m_command # type: uvm_tlm_command_e

m_data # type: List[int]

m_length # type: int

m_response_status # type: uvm_tlm_response_status_e

m_dmi # type: bool

m_byte_enable # type: List[int]

unsigned m_byte_enable_length # type: int

m_streaming_width # int

The data types of most members translate directly into uvm-python.

Unsigned int in SystemC become int in

Python. m_data and m_byte_enable, which are defined as type

char in SystemC, are defined as List of ints.

uvm_tlm_command_e and uvm_tlm_response_status_e are enumerated types.

They are defined as:

class uvm_tlm_command_e(Enum):

UVM_TLM_READ_COMMAND = auto()

UVM_TLM_WRITE_COMMAND = auto()

UVM_TLM_IGNORE_COMMAND = auto()

class uvm_tlm_response_status_e(IntEnum):

OK_RESPONSE = 1

INCOMPLETE_RESPONSE = 0

GENERIC_ERROR_RESPONSE = -1

ADDRESS_ERROR_RESPONSE = -2

COMMAND_ERROR_RESPONSE = -3

BURST_ERROR_RESPONSE = -4

BYTE_ENABLE_ERROR_RESPONSE = -5

All of the members of the generic payload can be randomized.

This enables instances of the generic payload to be randomized.

uvm-python allows arrays, including dynamic arrays to be

randomized.

2.4.1.2 Accessors¶

In SystemC, all of the attributes are private and are accessed through accessor methods. In Python, this restriction is removed. The following access methods are implemented:

def uvm_tlm_command_e get_command();

def void set_command(uvm_tlm_command_e command);

def bit is_read();

def void set_read();

def bit is_write();

def void set_write();

def void set_address(bit [63:0] addr);

def bit[63:0] get_address();

def void get_data (output byte p []);

def void set_data_ptr(ref byte p []);

def int unsigned get_data_length();

def void set_data_length(int unsigned length);

def int unsigned get_streaming_width();

def void set_streaming_width(int unsigned width);

def void get_byte_enable(output byte p[]);

def void set_byte_enable(ref byte p[]);

def int unsigned get_byte_enable_length();

def void set_byte_enable_length(int unsigned length);

def void set_dmi_allowed(bit dmi);

def bit is_dmi_allowed();

def uvm_tlm_response_status_e get_response_status();

def void set_response_status(uvm_tlm_response_status_e status);

def bit is_response_ok();

def bit is_response_error();

def string get_response_string();

The accessor functions let you set and get each of the members of the generic payload. This implies a slightly different use model for the generic payload than in SystemC. The way the generic payload is defined in SystemC does not encourage you to create new transaction types derived from uvm_tlm_generic_payload. Instead, you would use the extensions mechanism (see Section 2.4.1.3). Thus, in SystemC, none of the accessors are virtual.

In uvm-python, an important use model is to add randomization

constraints to a transaction type. This is most often done with

inheritance—take a derived object and add constraints to a base

class. These constraints can further be modified or extended by

deriving a new class, and so on. To support this use model, the

accessor functions are virtual, and the members are protected and not

local.

2.4.1.3 Extensions¶

The generic payload extension mechanism is very similar to the one used in SystemC; minor differences exist simply due to the lack of function templates in Python. Extensions are used to attach additional application-specific or bus-specific information to the generic bus transaction described in the generic payload.

An extension is an instance of a user-defined container class based on the uvm_tlm_extension class. The set of extensions for any particular generic payload object are stored in that generic payload object instance. A generic payload object may have only one extension of a specific extension container type.

Each extension container type is derived from the uvm_tlm_extension class and contains any additional information required by the user:

class gp_Xs_ext(uvm_tlm_extension):

def __init__(string name = ""):

super().__init__(name)

self.Xmask = []

uvm_object_utils_begin(gp_Xs_ext)

uvm_field_int_array('Xmask', UVM_ALL_ON)

uvm_object_utils_end(gp_Xs_ext)

To add an extension to a generic payload object, allocate an instance of the extension container class and attach it to the generic payload object using the set_extension() method:

Xs = gp_Xs_ext()

gp.set_extension(Xs)

The static function ID() in the user-defined extension container class can be used as an argument to the function get_extension method to retrieve the extension (if any) of the corresponding container type— if it is attached to the generic payload object:

Xs = gp.get_extension(gp_Xs_ext.ID)

The following methods are also available in the generic payload for managing extensions:

get_num_extensions()

clear_extension()

clear_extensions()

clear_extension() removes any extension of a specified type. clear_extensions() removes all extension containers from the generic payload.

2.4.2 Core Interfaces and Ports¶

In the uvm-python implementation of TLM-2.0, we have provided only

the basic transport interfaces. They are defined in the uvm_tlm_if#()

class:

class uvm_tlm_if():

The interface class is parameterized with the type of the transaction object that will be transported across the interface and the type of the phase enum. The default transaction type is the generic payload. The default phase enum is:

typedef enum {

UNINITIALIZED_PHASE, BEGIN_REQ, END_REQ, BEGIN_RESP, END_RESP

} uvm_tlm_phase_e;

Each of the interface methods take a handle to the transaction to be transported and a handle to a timescale- independent time value object. In addition, the nonblocking interfaces take a reference argument for the phase:

virtual function uvm_tlm_sync_e nb_transport_fw(

T t, ref P p, input uvm_tlm_time delay

);

virtual function uvm_tlm_sync_e nb_transport_bw(

T t, ref P p, input uvm_tlm_time delay

);

virtual task b_transport(T t, uvm_tlm_time delay);

In SystemC, the transaction argument is of type T&. Passing a handle to a class in SystemVerilog most closely represents the semantics of T& in SystemC. One implication in SystemVerilog is transaction types cannot be scalars. If the transaction argument was qualified with ref, indicating it was a reference argument, then it would be possible to use scalar types for transactions. However, that would also mean downstream components could change the handle to a transaction. This violates the required semantics in TLM-2.0 as stated in rule 4.1.2.5-b of the TLM-2.0 LRM, which is quoted here.

“If there are multiple calls to nb_transport associated with a given transaction instance, one and the same transaction object shall be passed as an argument to every such call. In other words, a given transaction instance shall be represented by a single transaction object.”

The phase and delay arguments may change value. These are also references in SystemC; e.g., P& and sc_time&. However, phase is a scalar, not a class, so the best translation is to use the ref qualifier to ensure the same object is used throughout the call sequence.

The uvm_tlm_time argument, which is present on all the interfaces, represents time. In the SystemC TLM-2.0 specification, this argument is reference to an sc_time variable, which lets the value change on either side. This was translated to a class object in SystemVerilog in order to manage timescales in different processes. Times passed through function calls are not automatically scaled. See Section 2.4.6 for more details.

An important difference between TLM-1 and TLM-2.0 is the TLM-2.0 interfaces pass transactions by reference and not by value. In SystemC, transactions in TLM-1 were passed as const references and in TLM-2.0 just as references. This allows the transaction object to be modified without copying the entire transaction. The result is much higher performance characteristics as a lot of copying is avoided. Another result is any object that has a handle to a transaction may modify it. However, to adhere to the semantics of the TLM-2.0 interfaces, these modifications must be made within certain rules and in concert with notifications made via the return enum in the ‘nb_*’ interfaces and the phase argument.

2.4.3 Blocking Transport¶

The blocking transport is implemented as follows:

async def b_transport(t, delay):

The b_transport task transports a transaction from the initiator to the target in a blocking fashion. The call to b_transport by the initiator marks the first timing point in the execution of the transaction. That first timing point may be offset from the current simulation by the delay value specified in the delay argument. The return from b_transport by the target marks the final timing point in the execution of the transaction. That last timing point may be offset from the current simulation time by the delay value specified in the delay argument. Once the task returns, the transaction has been completed by the target. Any indication of success or failure must be annotated in the transaction object by the target.

The initiator may read or modify the transaction object before the call to b_transport and after its return, but not while the call to b_transport is still active. The target may modify the transaction object only while the b_transport call is active and must not keep a reference to it after the task return. The initiator is responsible for allocating the transaction object before the call to b_transport. The same transaction object may be reused across b_transport calls.

2.4.4 Nonblocking Transport¶

The blocking transport is implemented using two interfaces:

function uvm_tlm_sync_e nb_transport_fw(T t, ref P p, input

uvm_tlm_time delay);

function uvm_tlm_sync_e nb_transport_bw(T t, ref P p, input

uvm_tlm_time delay);

nb_transport_fw transports a transaction in the forward direction, that is from the initiator to the target (the forward path). nb_transport_bw does the reverse, it transports a transaction from the target back to the initiator (the backward path). An initiator and target will use the forward and backward paths to update each other on the progress of the transaction execution. Typically, nb_transport_fw is called by the initiator whenever the protocol state machine in the initiator changes state and nb_transport_bw is called by the target whenever the protocol state machine in the target changes state.

The ‘nb_*’ interfaces each return an enum uvm_tlm_sync_e. The possible enum values and their meanings are shown in Table 2.

Table 2—uvm_tlm_sync_e enum Description

Enum value |

Interpretation |

UVM_TLM_ACCEPTED: |

Transaction has been accepted. Neither the transaction object, the phase nor the delay arguments have been modified. |

UVM_TLM_UPDATED: |

Transaction has been modified. The transac tion object, the phase or the delay arguments may have been modified. |

UVM_TLM_COMPLETED: |

Transaction execution has completed. The transaction object, the phase or the delay arguments may have been modified. There will be no further transport calls associated with this transaction. |

The P argument of nb_transport_fw and nb_transport_bw represents the transaction phase. This can be a user-defined type that is specific to a particular protocol. The default type is uvm_tlm_phase_e, whose values are shown in Table 3. These can be used to implement the Base Protocol.

Table 3—uvm_tlm_phase_e Description

Enum value |

Interpretation |

UNITIALIZED_PHASE |

Phase has not yet begun |

BEGIN_REQ |

Request has begun |

END_REQ |

Request has completed |

BEGIN_RESP |

Response has begun |

END_RESP |

Response has terminated |

The first call to nb_transport_fw by the initiator marks the first timing point in the transaction execution. Subsequent calls to nb_transport_fw and nb_transport_bw mark additional timing points in the transaction execution. The last timing point is marked by a return from nb_transport_fw or nb_transport_bw with UVM_TLM_COMPLETED. All timing points may be offset from the current simulation time by the delay value specified in the delay argument. An nb_transport_fw call on the forward path shall under no circumstances directly or indirectly make a call to nb_transport_bw on the backward path, and vice versa.

The value of the phase argument represents the current state of the protocol state machine. Any change in the value of the transaction object should be accompanied by a change in the value of phase. When using the Base Protocol, successive calls to nb_transport_fw or nb_transport_bw with the same phase value are not permitted.

The initiator may modify the transaction object, the phase and the delay arguments immediately before calls to nb_transport_fw and before it returns from nb_transport_bw only. The target may modify the transaction object, the phase and the delay arguments immediately before calls to nb_transport_bw and before it returns from nb_transport_fw only. The transaction object, phase and delay arguments may not be otherwise modified by the initiator or target.

The initiator is responsible for allocating the transaction object before the first call to nb_transport_fw. The same transaction object is used by all of the forward and backward calls during its execution. That transaction object is alive for the entire duration of the transaction until the final timing point. The same transaction object may be reused across different transaction execution that do not overlap in time.

2.4.5 Sockets¶

In TLM-1, the primary means of making a connection between two processes is through ports and exports, whereas in TLM-2.0 this done through sockets. A socket is like a port or export; in fact, it is derived from the same base class as ports and export, namely uvm_port_base. However, unlike a port or export a socket provides both a forward and backward path. Thus, you can enable asynchronous (pipelined) bi-directional communication by connecting sockets together. To enable this, a socket contains both a port and an export.

Components that initiate transactions are called initiators and components that receive transactions sent by an initiator are called targets. Initiators have initiator sockets and targets have target sockets. Initiator sockets can only connect to target sockets; target sockets can only connect to initiator sockets.

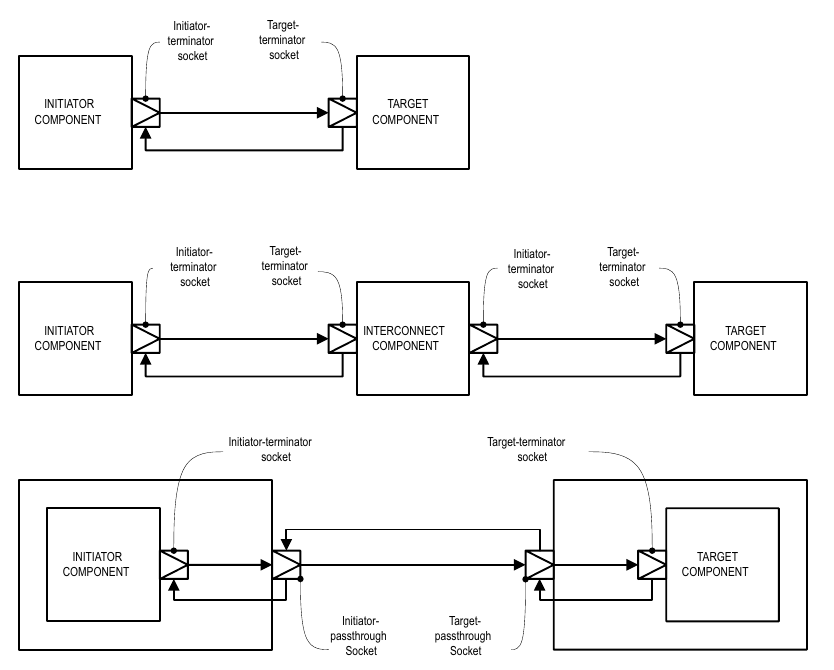

Figure 9 shows the diagramming of socket connections. The socket symbol is a box with an isosceles triangle with its point indicating the data and control flow direction of the forward path. The backward path is indicated by an arrow connecting the target socket back to the initiator socket. Section 3.4 of the TLM-2.0 LRM fully explains sockets, initiators, targets, and interconnect components.

Socket Connections¶

Sockets come in several flavors: Each socket is an initiator or a target, a passthrough, or a terminator. Furthermore, any particular socket implements either blocking interfaces or nonblocking interfaces. Terminator sockets are used on initiators and targets as well as interconnect components as shown in Figure 9. Passthrough sockets are used to enable connections to cross hierarchical boundaries.

The cross product of {initiator, target} X {terminator, passthrough} X {blocking, nonblocking} yields eight different kinds of sockets. The class definitions for these sockets are as follows:

class uvm_tlm_nb_passthrough_initiator_socket #(type T=uvm_tlm_generic_payload,

type P=uvm_tlm_phase_e) extends

uvm_tlm_nb_passthrough_initiator_socket_base #(T,P);

class uvm_tlm_nb_passthrough_target_socket#(

type T=uvm_tlm_generic_payload,

type P=uvm_tlm_phase_e

) extends uvm_tlm_nb_passthrough_target_socket_base #(T,P);

class uvm_tlm_b_passthrough_initiator_socket #(

type T=uvm_tlm_generic_payload

) extends

uvm_tlm_b_passthrough_initiator_socket_base #(T);

class uvm_tlm_b_passthrough_target_socket #(

type T=uvm_tlm_generic_payload

)

extends uvm_tlm_b_passthrough_target_socket_base #(T);

class uvm_tlm_b_target_socket #(

type T=uvm_tlm_generic_payload,

type IMP=int

) extends uvm_tlm_b_target_socket_base #(T);

class uvm_tlm_b_initiator_socket #(type T=uvm_tlm_generic_payload)

extends uvm_tlm_b_initiator_socket_base #(T);

class uvm_tlm_nb_target_socket #(

type T=uvm_tlm_generic_payload,

type P=uvm_tlm_phase_e, type IMP=int

) extends uvm_tlm_nb_target_socket_base #(T,P);

class uvm_tlm_nb_initiator_socket #(

type T=uvm_tlm_generic_payload,

type P=uvm_tlm_phase_e, type IMP=int

) extends uvm_tlm_nb_initiator_socket_base #(T,P);

Table 4 shows the different kinds of sockets and how they are constructed.

Table 4—Socket Construction

Socket |

Blocking |

Nonblocking |

initiator |

IS-A forward port |

IS-A forward port; HAS-A backward imp |

target |

IS-A forward imp |

IS-A forward imp; HAS-A backward port |

passthrough initiator |

IS-A forward port |

IS-A forward port; HAS-A backward export |

passthrough target |

IS-A forward export |

IS-A forward port; HAS-A backward export |

IS-A and HAS-A are types of object relationships. IS-A refers to the inheritance relationship and HAS-A refers to the ownership relationship. For example, if you say D is a B, it means D is derived from base B. If you say object A HAS-A B, it means B is a member of A.

Each <socket_type>::connect() calls super.connect(), which performs all the connection mechanics. For the nonblocking sockets which have a secondary port/export for the backward path, connect() is called on the secondary port/export to form a backward connection.

Each socket type provides an implementation of the connect() method. Connection is defined polymorphically using the base class type as the argument:

def connect(provider)

Each implementation of connect() in each socket type does run-time type checking to ensure it is connected to allowable socket types. For example, an initiator socket can connect to an initiator passthrough socket, a target passthrough socket, or a target socket. It cannot connect to another initiator socket. These kinds of checks are performed for each socket type.

2.4.6 Time¶

Warning

This is section on Time must be revised for uvm-python.

Integers are not sufficient on their own to represent time without any ambiguity; you need to know the scale of that integer value, which is conveyed outside of the integer. In SystemVerilog, this is based on the timescale that was active when the code was compiled. SystemVerilog properly scales time literals, but not integer values because it does not know the difference between an integer that carries an integer value and an integer that carries a time value. time variables are simply 64-bit integers, they are not scaled back and forth to the underlying precision. Here is a short example that illustrates part of the problem:

\`timescale 1ns/1ps

module m();

time t;

initial begin

#1.5;

$write("T=%f ns (Now should be 1.5)\n", $realtime());

t = 1.5;

#t; // 1.5 will be rounded to 2

$write("T=%f ns (Now should be 3.0)\n", $realtime());

#10ps;

$write("T=%f ns (Now should be 3.010)\n", $realtime());

t = 10ps; // 0.010 will be converted to int (0)

#t;

$write("T=%f ns (Now should be 3.020)\n", $realtime());

end

endmodule

yields:

T=1.500000 ns (Now should be 1.5)

T=3.500000 ns (Now should be 3.0)

T=3.510000 ns (Now should be 3.010)

T=3.510000 ns (Now should be 3.020)

Within SystemVerilog, we have to worry about different time scales and precision. Because each endpoint in a socket could be coded in different packages and, thus, be executing under different timescale directives, a simple integer cannot be used to exchange time information across a socket.

For example:

\`timescale 1ns/1ps

package a_pkg; class a;

function void f(inout time t);

t += 10ns;

endfunction endclass

endpackage

\`timescale 1ps/1ps

program p;

import a_pkg::*;

time t = 0;

initial begin

a A = new;

A.f(t);

#t;

$write("T=%0d ps (Should be 10,000)\n", $time());

end

endprogram

yields:

T=10 ps (Should be 10,000)

Scaling is needed every time you make a procedural call to code that may interpret a time value in a different timescale. Using the uvm_tlm_time type:

`timescale 1ns/1ps

package a_pkg;

import uvm_pkg::*;

class a;

function void f(uvm_tlm_time t);

t.incr(10ns, 1ns);

endfunction

endclass

endpackage

`timescale 1ps/1ps

program p;

import uvm_pkg::*;

import a_pkg::*;

uvm_tlm_time t = new;

initial begin

a A = new;

A.f(t);

#(t.get_realtime(1ns));

$write("T=%0d ps (Should be 10,000)\n", $time());

end

endprogram

yields:

T=10000 ps (Should be 10,000)

To solve these problems, the uvm_tlm_time class contains the scaling information so that as time information is passed between processes, which may be executing under different time scales, the time can be scaled properly in each environment.

2.4.7 Use Models¶

Since sockets are derived from UVMPortBase, they are created and

connected in the same way as port and exports. You can create them in

the build phase and connect them in the connect phase by calling

UVMPortBase.connect(). Initiator and target termination sockets are the end

points of any connection. There can be an arbitrary number of

passthrough sockets in the path between the initiator and target.

Some socket types must be bound to imps—implementations of the transport tasks and functions. Blocking terminator sockets must be bound to an implementation of b_transport(), for example. Nonblocking initiator sockets must be bound to an implementation of nb_transport_bw and nonblocking target sockets must be bound to an implementation of nb_transport_fw. Typically, the task or function is implemented in the component where the socket is instantiated and the component type and instance are provided to complete the binding.

Consider, for example, a consumer component with a blocking target socket:

class consumer (UVMComponent);

def __init__(self, name, parent):

super().__init__(name, parent)

self.target_socket = None

def build_phase(self, phase):

self.target_socket = uvm_tlm_b_target_socket("target_socket", self, self);

# Note: async must be used to allow usage of await

async def b_transport(self, t, delay):

await Timer(5)

uvm_info("consumer", t.convert2string(), UVM_LOW)

The interface task b_transport is implemented in the consumer component. The consumer component type is used in the declaration of the target socket, which informs the socket object of the type of the object containing the interface task, in this case b_transport(). When the socket is instantiated this is passed in twice, once as the parent, just like any other component instantiation, and again to identify the object that holds the implementation of b_transport(). Finally, in order to complete the binding, an implementation of b_transport() must be present in the consumer component.

Any component that has a blocking termination socket, nonblocking initiator socket, or nonblocking termination socket must provide implementations of the relevant components. This includes initiator and target components, as well as interconnect components that have these kinds of sockets. Components with passthrough sockets do not need to provide implementations of any sort. Of course, they must ultimately be connected to sockets that do provide the necessary implementations.

3. Developing Reusable Verification Components¶

This chapter describes the basic concepts and components that make up a typical verification environment. It also shows how to combine these components using a proven hierarchical architecture to create reusable verification components. The sections in this chapter follow the same order you should follow when developing a verification component:

Modeling Data Items for Generation

Transaction-Level Components

Creating the Driver

Creating the Sequencer

Creating the Monitor

Instantiating Components

Creating the Agent

Creating the Environment

Enabling Scenario Creation

Managing End of Test

Implementing Checks and Coverage

NOTE—This chapter builds upon concepts described in Chapter 1 and Chapter 2.

3.1 Modeling Data Items for Generation¶

Data items:

— Are transaction objects used as stimulus to the device under test (DUT). — Represent transactions that are processed by the verification environment. — Are instances of classes that you define (“user-defined” classes). — Capture and measure transaction-level coverage and checking.

NOTE—The UVM Class Library provides the UVMSequenceItem base class. Every user-defined data item should be derived directly or indirectly from this base class.

To create a user-defined data item:

a) Review your DUT’s transaction specification and identify the application-specific properties, constraints, tasks, and functions. b) Derive a data item class from the UVMSequenceItem base class (or a derivative of it). c) Define a constructor for the data item. d) Add control fields (“knobs”) for the items identified in Step (a) to enable easier test writing. e) Use UVM field macros to enable printing, copying, comparing, and so on. f) Define do functions for use in creation, comparison, printing, packing, and unpacking of transaction data as needed (see Section 6.7).

UVM has built-in automation for many service routines that a data item needs. For example, you can use:

- print() to print a data item.

- copy() to copy the contents of a data item.

- compare() to compare two similar objects.

UVM allows you to specify the automation needed for each field and to use a built-in, mature, and consistent implementation of these routines.

To assist in debugging and tracking transactions, the uvm_transaction base class provides access to a unique transaction number via the get_transaction_id() member function. In addition, the UVMSequenceItem base class (extended from uvm_transaction) also includes a get_transaction_id() member function, allowing sequence items to be correlated to the sequence that generated them originally.

The class simple_item in this example defines several random variables and class constraints. The UVM mixin functions implement various utilities that operate on this class, such as copy, compare, print, and so on. In particular, the uvm_object_utils function registers the class type with the common factory:

1 class simple_item(UVMSequenceItem)

2 def __init__(self name="simple_item"):

3 super().__init__(name)

4 self.addr = 0x0

5 self.randr('addr', range(0x2000))

6 self.data = 0x0

7 self.randr('data', range(0x1000))

8 self.delay = 0x0

9 self.randr('delay', range(1 << 32 - 1))

10 # UVM automation macros for general objects

11 uvm_object_utils_begin(simple_item)

12 uvm_field_int('addr', UVM_ALL_ON)

13 uvm_field_int('data', UVM_ALL_ON)

14 uvm_field_int('delay', UVM_ALL_ON)

15 uvm_object_utils_end

Line 1 Derives data items from UVMSequenceItem so they can be

generated in a procedural sequence. See Section 3.10.2 for more

information.

Line 5,Line 7 and Line 9

Add constraints to a data item definition in order to:

Reflect specification rules. In this example, the address must be less than 0x2000. Specify the default distribution for generated traffic. For example, in a typical test most transactions should be legal.

Line 11-Line 15 Use the UVM functions to automatically implement

functions such as copy(), compare(), print(), pack(), and so on.

Refer to “Macros” in the UVM 1.2 Class Reference for information on

the uvm_object_utils_begin, uvm_object_utils_end, uvm_field_*,

and their associated macros.

3.1.1 Inheritance and Constraint Layering¶

In order to meet verification goals, the verification component user might need to adjust the data-item generation by adding more constraints to a class definition. In SystemVerilog, this is done using inheritance. The following example shows a derived data item, word_aligned_item, which includes an additional constraint to select only word-aligned addresses:

class word_aligned_item extends simple_item;

constraint word_aligned_addr { addr[1:0] == 2'b00; }

`uvm_object_utils(word_aligned_item)

// Constructor

function new (string name = "word_aligned_item");

super.new(name);

endfunction : new

endclass : word_aligned_item

To enable this type of extensibility:

— The base class for the data item (simple_item in this chapter) should use virtual methods to allow derived classes to override functionality. — Make sure constraint blocks are organized so that they are able to override or disable constraints for a random variable without having to rewrite a large block. — Note that fields can be declared with the protected or local keyword to restrict access to properties. This, however, will limit the ability to constrain them with an inline constraint.

3.1.2 Defining Control Fields (“Knobs”)¶

The generation of all values of the input space is often impossible and usually not required. However, it is important to be able to generate a few samples from ranges or categories of values. In the simple_item example in Section 3.1, the delay property could be randomized to anything between zero and the maximum unsigned integer. It is not necessary (nor practical) to cover the entire legal space, but it is important to try back-to-back items along with short, medium, and large delays between the items, and combinations of all of these. To do this, define control fields (often called “knobs”) to enable the test writer to control these variables. These same control knobs can also be used for coverage collection. For readability, use enumerated types to represent various generated categories.

Knobs Example:

typedef enum {ZERO, SHORT, MEDIUM, LARGE, MAX} simple_item_delay_e;

class simple_item extends UVMSequenceItem;

rand int unsigned addr;

rand int unsigned data;

rand int unsigned delay;

rand simple_item_delay_e delay_kind; // Control field

// UVM automation macros for general objects

`uvm_object_utils_begin(simple_item)

`uvm_field_int(addr, UVM_ALL_ON)

`uvm_field_enum(simple_item_delay_e, delay_kind, UVM_ALL_ON)

`uvm_object_utils_end

constraint delay_order_c { solve delay_kind before delay; }

constraint delay_c {(delay_kind == ZERO) -> delay == 0;

(delay_kind == SHORT) -> delay inside { [1:10] };

(delay_kind == MEDIUM) -> delay inside { [11:99] };

(delay_kind == LARGE) -> delay inside { [100:999] };

(delay_kind == MAX ) -> delay == 1000;

delay >=0; delay <= 1000;

}

endclass : simple_item

Using this method allows you to create more abstract tests. For example, you can specify distribution as:

constraint delay_kind_d {

delay_kind dist {ZERO:=2, SHORT:=1, MEDIUM:=1, LONG:=1, MAX:=2};

}

When creating data items, keep in mind what range of values are often used or which categories are of interest to that data item. Then add knobs to the data items to simplify control and coverage of these data item categories.

3.2 Transaction-Level Components¶

As discussed in Chapter 2, TLM interfaces in UVM provide a consistent set of communication methods for sending and receiving transactions between components. The components themselves are instantiated and connected in the testbench, to perform the different operations required to verify a design. A simplified testbench is shown in Figure 10 (for simplicity, typical containers like environment and agents are not shown here).

Simplified Transaction-Level Testbench¶

The basic components of a simple transaction-level verification environment are:

a) A stimulus generator (sequencer) to create transaction-level traffic to the DUT. b) A driver to convert these transactions to signal-level stimulus at the DUT interface. c) A monitor to recognize signal-level activity on the DUT interface and convert it into transactions. d) An analysis component, such as a coverage collector or scoreboard, to analyze transactions.

As we shall see, the consistency and modularity of the TLM interfaces in UVM allow components to be reused as other components are replaced and/or encapsulated. Every component is characterized by its interfaces, regardless of its internal implementation (see Figure 11). This chapter discusses how to encapsulate these types of components into a proven architecture, a verification component, to improve reuse even further.

Highly Reusable Verification Component Agent¶

Figure 11 shows the recommended grouping of individual components into a reusable interface-level verification component agent. Instead of reusing the low-level classes individually, the developer creates a component that encapsulates it’s sub-classes in a consistent way. Promoting a consistent architecture makes these components easier to learn, adopt, and configure.

3.3 Creating the Driver¶

The driver’s role is to drive data items to the bus following the interface protocol. The driver obtains data items from the sequencer for execution. The UVM Class Library provides the uvm_driver base class, from which all driver classes should be extended, either directly or indirectly. The driver has a TLM port through which it communicates with the sequencer (see the example below). The driver may also implement one or more of the run-time phases (run and pre_reset - post_shutdown) to refine its operation.

To create a driver:

Derive from the uvm_driver base class.

- If desired, add UVM

infrastructure macros for class properties to implement utilities for printing, copying, comparing, and so on.

- Obtain the next data item from the

sequencer and execute it as outlined above.

- Declare a virtual

interface in the driver to connect the driver to the DUT.

Refer to Section 3.10.2 for a description of how a sequencer, driver, and sequences synchronize with each other to generate constrained random data.

The class simple_driver in the example below defines a driver class.

The example derives simple_driver from uvm_driver (parameterized to

use the simple_item transaction type) and uses the methods in the

seq_item_port object to communicate with the sequencer. As always,

include a constructor and the uvm_component_utils mixin to register

the driver type with the common factory.

1class simple_driver(UVMDriver):

2 simple_item s_item;

3 virtual dut_if vif;

4

5 # Constructor

6 def __init__(self, name="simple_driver", parent):

7 super().__init__(name, parent);

8

9

10 def build_phase(self, phase):

11 inst_name = ""

12 super().build_phase(phase);

13 if(!UVMConfigDb#(virtual dut_if)::get(this, "","vif",vif))

14 uvm_fatal("NOVIF", {"virtual interface must be set for: ",

15 get_full_name(),".vif"});

16

17

18 async def run_phase(self, phase):

19 while True:

20 # Get the next data item from sequencer (may block).

21 seq_item_port.get_next_item(s_item);

22 # Execute the item.

23 drive_item(s_item);

24 seq_item_port.item_done(); // Consume the request.

25

26

27 async def drive_item(self, item):

28 ... # Add your logic here.

29

30

31uvm_component_utils(simple_driver)

Line 1 Derive the driver.

Line 5 Add UVM infrastructure macro.

Line 13 Get the resource that defines the virtual interface

Line 22 Call get_next_item() to get the next data item for execution from the sequencer.

Line 25 Signal the sequencer that the execution of the current data item is done.

Line 30 Add your application-specific logic here to execute the data item.

More flexibility exists on connecting the drivers and the sequencer. See Section 3.5.

3.4 Creating the Sequencer¶

The sequencer generates stimulus data and passes it to a driver for

execution. The UVM Class Library provides the UVMSequencer base

class, which is parameterized by the request and response item types.

The UVMSequencer base class contains all of the base functionality

required to allow a sequence to communicate with a driver. The

uvm_sequencer gets instantiated directly, with appropriate

parameterization as shown in Section 3.8.1, Line 3. In the class

definition, by default, the response type is the same as the request

type. If a different response type is desired, the optional second

parameter must be specified for the uvm_sequencer base type:

uvm_sequencer #(simple_item, simple_rsp) sequencer;

Refer to Section 3.10.2 for a description of how a sequencer, driver, and sequences synchronize with each other to generate constrained-random data.

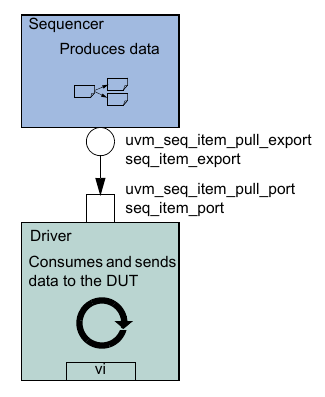

3.5 Connecting the Driver and Sequencer¶

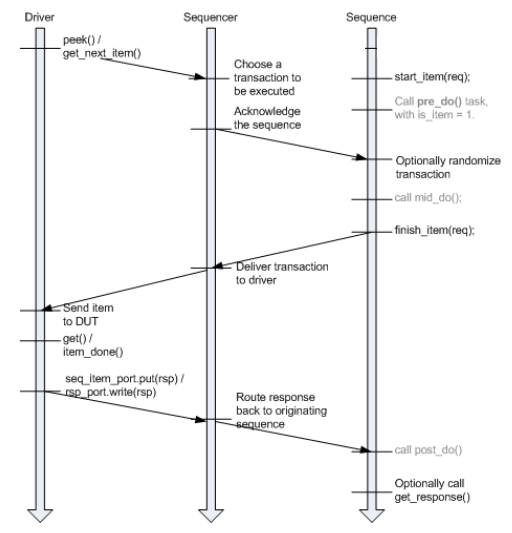

The driver and the sequencer are connected via TLM, with the driver’s seq_item_port connected to the sequencer’s seq_item_export (see Figure 12). The sequencer produces data items to provide via the export. The driver consumes data items through its seq_item_port and, optionally, provides responses. The component that contains the instances of the driver and sequencer makes the connection between them. See Section 3.8.

Sequencer-Driver Interaction¶

The seq_item_port in UVMDriver defines the set of methods used by

the driver to obtain the next item in the sequence. An important part

of this interaction is the driver’s ability to synchronize to the

bus, and to interact with the sequencer to generate data items at the

appropriate time. The sequencer implements the set of methods that

allows flexible and modular interaction between the driver and the

sequencer.

3.5.1 Basic Sequencer and Driver Interaction¶

Basic interaction between the driver and the sequencer is done using the tasks get_next_item() and item_done(). As demonstrated in the example in Section 3.3, the driver uses get_next_item() to fetch the next randomized item to be sent. After sending it to the DUT, the driver signals the sequencer that the item was processed using item_done().Typically, the main loop within a driver resembles the following pseudo code:

while True:

t = []

await self.get_next_item(t) # Send item following the protocol. item_done();

req = t[0]

end

NOTE—get_next_item() is blocking until an item is provided by the

sequences running on that sequencer.

3.5.2 Querying for the Randomized Item¶

In addition to the get_next_item() task, the UVMSeqItemPullPort

class provides another task, try_next_item(). This task will return

in the same simulation step if no data items are available for

execution. You can use this task to have the driver execute some idle

transactions, such as when the DUT has to be stimulated when there

are no meaningful data to transmit. The following example shows a

revised

implementation of the run_phase() task in the previous example (in

Section 3.3), this time using try_next_item() to drive idle

transactions as long as there is no real data item to execute:

async def run_phase(self, phase):

while True:

# Try the next data item from sequencer (does not block).

t = []

await seq_item_port.try_next_item(t)

s_item = t[0] if len(t) > 0 else None

if s_item is None:

# No data item to execute, send an idle transaction. ...

end

else:

# Got a valid item from the sequencer, execute it. ...

# Signal the sequencer; we are done.

seq_item_port.item_done();

3.5.3 Fetching Consecutive Randomized Items¶